1920

-

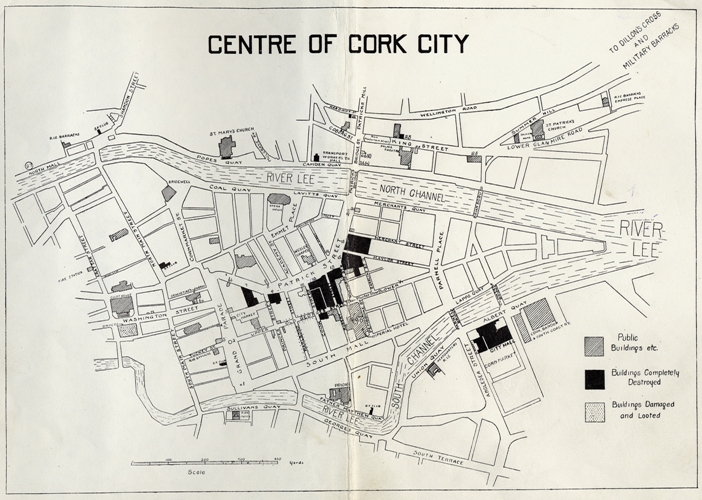

The Capture of Carrigtwohill RIC Barracks

Carrigtwohill RIC personnel

3 January 1920The first major action of 1920 in Cork came with the Capture of the Carrigtwohill RIC Barracks in East Cork. The siege to take the barracks would be the first operation of the Midleton and Cobh IRA Active Service Units under the command of Commandant Michael Leahy O/C of the East Cork Volunteers. Due to the early attacks on isolated RIC Barracks throughout 1919 in early January of 1920, the RIC had begun fortifying their barracks against attack by incorporating steel shutters covering the windows. These steel covers had loop-holes cut out of them in order to allow the occupants of the barracks to fire out from secure cover. The RIC was also being equipped with surplus army equipment such as sandbags, barbed wire and weapons.

It is interesting to note that Michael Leahy stated that there were 35 Midleton Volunteers, 40 Cobh Volunteers and around 35 Knockraha Volunteers involved in the operation. Most of the Volunteers were blocking the roads with possibly only 17 Volunteers attacking the barracks. The Newspaper reports at the time claim that only 5 RIC constables and 1 RIC Sergeant were present. The Volunteers set about blocking roads to the village by felling trees as well as cutting telephone communications to the barracks. As the assault began the steel shutters prevented the Volunteers from gaining entrance to the Barracks. A team of Volunteers took about an hour to bore five holes in the stone wall in order to place the gelignite explosives. The rest of the attacking force continued to fire on the barracks in order to cover the men laying the explosives. During this time the RIC returned fire and sent up Verey flare lights to call for assistance. As the volunteers breached the Barracks the RIC retreated upstairs before surrendering. The volunteers secured rifles, grenades and ammunition from the barracks before releasing the captured RIC Constables.

A campaign of attacks and sieges had begun with no less than four other barracks including Kilmurray, Inchigeela, Carrignavar and Killumney, attacked on the same night.

References

Cork Examiner, 5 January 1920 -

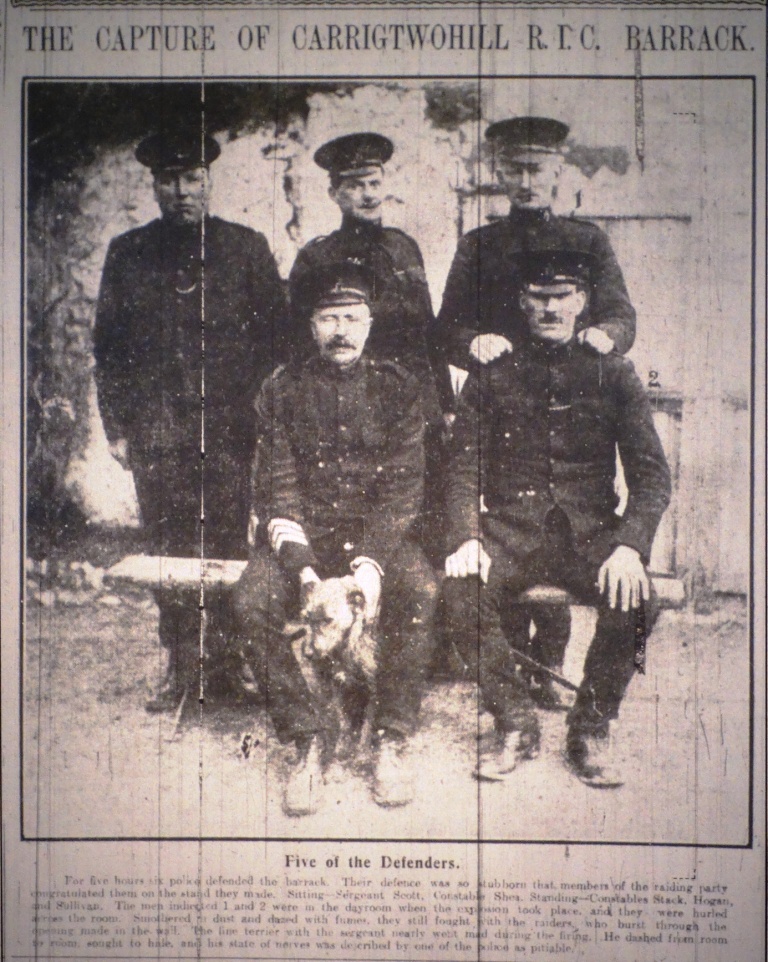

The Capture of Castlemartyr RIC Barracks

Castlemartyr Barracks

9 February 1920On 9 February the Castlemartyr RIC Barracks was raided by a party of Irish Volunteers lead by Captain Diarmuid Hurley. The attack was unplanned and only a small party of 10-14 volunteers were available to Captain Hurley. The Castlemartyr Barracks was a large building, still standing today, which was garrisoned by eight RIC personnel including two sergeants. According to sources, two of the garrison, a Sergeant O’Brien and Constable Collins, incidentally a cousin of Michael Collins, were held up on the main Midleton road after returning from policing a fair in the town. Most of the rest of the Garrison were out of the Barracks at dinner or on leave, leaving a Sergeant O’Sullivan and Constable Lee manning the Barracks.

With the garrison low on numbers the volunteers attempted to gain entrance by using Sergeant O’Brien to open the door but both RIC men refused to betray their comrades in the barracks. Captain Hurley thus attempted to impersonate the Sergeant calling on the main door to be opened. Constable Lee proceeded to unfasten the main bolts on the steel door but left the chain on to keep the door somewhat secure. As the door began to open slightly Captain Diarmuid Hurley placed his foot in-between the door and the door frame so that it could not be closed again. Sensing danger Constable Lee emptied his revolver in the opening of the door. Captain Hurley broke the chain on the door and grappled with the constable striking him in the eye with the butt of his revolver. The volunteers burst in and Sergeant O’Sullivan surrendered. The Volunteers made off with 8 rifles, 6 revolvers, 8 bayonets, some Mills bombs and around 2,000 rounds of ammunition

By April of 1920 over 500 isolated RIC barracks were abandoned leaving large swathes of the countryside in the hands of the IRA. The IRA had destroyed over 400 of these by the end of June to prevent their subsequent reuse.

References

Cork Examiner, 10 February 1920 -

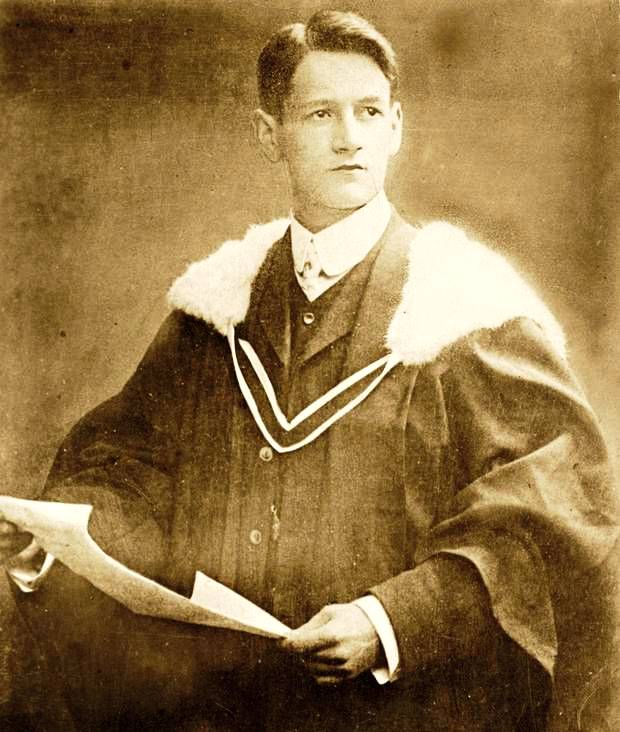

The Murder of Lord Mayor Tomás MacCurtain

Tomás MacCurtain

20 March 1920In the early hours of 20 March 1920 the Lord Mayor of Cork Tomás MacCurtain was shot dead in his home by masked men. It was the morning of his thirty-sixth birthday. Tomás MacCurtain was the Lord Mayor of Cork and a member of Sinn Féin, he was also the Brigade Commander of the IRA No. 1 Cork Brigade. Tomás MacCurtain had become a clear target to British reprisals due to the public nature of his position as well as his well known republican connections. MacCurtain was murdered at his family home in a two-story building at 40, Thomas Davis Street. The bottom floor of the building housed the family clothing business while the top two floors were used as the family residence.

The night before his murder, Mr Tomás MacCurtain, was working late at Cork City Hall with the town clerk, Con Harrington. Tadhg Barry came in to warn him that there would be reprisal set against him by the British if another RIC member was shot in Cork. As Mr MacCurtain made his way home he was approached and warned that a RIC Constable Murtagh had been shot on Popes Quay late on March 19th.

At approximately 1.00 am in the early hours of Saturday morning, 20 March, Tomás MacCurtain and his wife, Mrs Elizabeth MacCurtain, were woken from their sleep by loud knocking on the front door of the shop. Elizabeth MacCurtain insisted she would go to see who was at the door while Tomás MacCurtain got dressed. As she opened the door six men brandishing rifles and revolvers burst in the door demanding the Lord Mayor. Two held Mrs MacCurtain while the other four marched upstairs. Tomas MacCurtain was shot twice in his room while other members of his family were calling for help as the masked men fled. Later that day an RIC button and spent cartridges were found outside the MacCurtain address.

An inquest was completed on 17 April which had witnesses including 64 police, 31 civilians and 2 military personnel. The verdict given was that Mr Tomás MacCurtain was wilfully murdered, and that the murder was organised and carried out by the Royal Irish Constabulary, officially directed by the British government. It returned a verdict of wilful murder against David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of England; Lord French, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland; Ian Macpherson, late chief secretary of Ireland; acting Inspector General Smith, of the Royal Irish Constabulary; Divisional Inspector Clayton, of the Royal Irish Constabulary; District Inspector Swanzy, and some unknown members of the Royal Irish Constabulary.

References

Cork Examiner, 20 March – 20 April 1919 -

Cork Police Commissioner Shot Dead

Lt. Col. Gerard Bryce Ferguson Smyth

17 July 1920On 17 July 1920 the recently appointed Munster Divisional Police Commissioner, Lt. Col. Gerard Bryce Ferguson Smyth, was shot by the IRA in the Cork County Club. Lt Col. Gerard Bryce Ferguson Smyth was a decorated war hero of the First World War. In June 1920 Colonel Smyth was sent to Ireland at the height of the War of Independence and was seconded to the RIC. The reason behind the deliberate targeting of Lt. Col Smyth appears to have been for the shoot to kill policy he attempted to encourage in the RIC which led to the Listowel RIC Mutiny. Lt. Col. Smyth was known to be staying at the Cork County Club on the South Mall in Cork City centre.

The County Club in Cork was frequented by high-ranking military officers and people loyal to the Government. The staff were also considered to be loyalists and so the IRA found it very difficult to obtain information about the club and those who visited it. On the 17th a dozen members of the No.1 Brigade entered the County Club. One of the men walked up to Smyth and allegedly said: 'Your orders were to shoot on sight. You are in sight now so make ready', after which he was shot a number of times. RIC County Inspector Craig was wounded in the leg during the attack by a ricochet. The assailants then ran out of the club and mingled with the crowds coming out of cinemas nearby. On the following day General Strickland, Commander of British forces in the area, ordered a curfew and armoured cars and military police and soldiers patrolled the streets of Cork.

On 21 July 1920, Lt Col Smyth was buried at the public cemetery, Newry Road, Banbridge, Co. Down. After his death, three days of rioting took place in Belfast and a number of Catholics lost their lives. There was also rioting in Banbridge and Dromore, Co. Down, with one person being killed in Dromore.

References

Cork Examiner, 19 July 1920

County Club premises on South Mall, Cork

-

Lord Mayor Terence MacSwiney Arrested

Terence MacSwiney

12 August 1920On 20 March 1920, Terence MacSwiney was unanimously elected Lord Mayor of Cork by the city's Corporation, composed of representatives of Sinn Féin, the Redmond, O’Brien and Unionist parties. In the local elections in 1920 Sinn Fein secured 30 of the fifty six Cork City Council seats with the collapse in support for the Irish Parliamentary Party which supported constitutional nationalism. Terence MacSwiney was a well known republican and was the Commander of the No.1 Brigade of the Cork IRA following the death of Tomás MacCurtain. Due to the escalation of nationalist activity throughout Cork the British authorities sought to make an example. On Thursday 12 August 1920, the British Military surrounded Cork City Hall and arrested the Lord Mayor, Terence MacSwiney, and ten other prominent Sinn Féiners who were adjudicating in courts or acting as Officers of the Courts.

Two lorries arrived full of heavily armed British Military personnel at 7.30 pm. The British Military proceeded to surround City Hall with fixed bayonets and storm the building. This caused wide spread panic and large crowds assembled on Anglesea Street, Albert Quay and Lapps Quay to witness this event. The British Military closed off all streets surrounding City Hall and all traffic around the building stopped. The British Military then stormed City Hall with fixed bayonets as the crowds outside jeered in anger. More Lorries then arrived with more British Military. When the first two British soldiers entered the front door of City Hall, the Lord Mayor's attendants escorted him to the side of City Hall in hopes he would escape but he was captured. The Lord Mayor was then taken to Victoria Barracks before being moved to Cork County Gaol.

The Lord Mayor, Terence MacSwiney, stated that his arrest and the arrest of the other Council members was illegal and that he would take part in a hunger strike, which he began on the day of his arrest, until he was freed or would die in protest. Over 50 other political prisoners were also on hunger strike during this time in the County Gaol.

References

Cork Examiner, 13-14 August 1920 -

The Death of Terence MacSwiney

Terence MacSwiney and family

25 October 1920Terence MacSwiney had been arrested on August 12th by the British military on the charges of Sedition against the state. The charges that were laid against the Lord Mayor include;

- Being in possession of a RIC numeric Cipher at the time of his arrest.

- Having this under his control.

- Being in possession of a document containing statements likely to cause disaffection to his Majesty. This document was the resolution (an amended one) passed by the Corporation acknowledging the authority of, and pledging allegiance to Daíl Eireann.

- Possessing a copy of the speech the Lord Mayor made when elected as successor to Lord Mayor Mac Curtain.

Lieutenant Colonel James of the South Staffordshire Regiment headed the court martial. The Court Martial found Terence MacSwiney to be guilty of the latter three charges and he was sentenced to two years in Brixton prison. At the trial Mr MacSwiney, upon being asked if he would be represented, replied that ‘‘I would like to say a word about your proceedings here. The position is that I am Lord Mayor of Cork and Chief Magistrate of this city. I declare this court illegal, and that those who take part in it are liable to arrest under the laws of the Irish Republic”.

At the time of his Court Martial Terence MacSwiney had already begun a hunger strike in opposition to his arrest. Despite the Lord Mayor being gravely ill from his hunger strike he declared that he would continue the hunger strike until he was released or died of starvation. The British Government ignored the 1913 Prisoner Act that allowed for the release of gravely ill prisoners. They were determined to stand their ground with Terence MacSwiney and feared that releasing him would spark mutiny in Ireland, this was despite requests by King George V for his release. The Lord Mayor continued his hunger strike and after 74 days, on the 25 October, he passed away. Terence MacSwiney’s death was reported around the world and brought international attention to the fight for Irish independence

References

Cork Examiner, 12 August - 26 October 1920 -

Bloody Sunday

Black and Tans in Ireland

21 November 1920Possibly the most violent day of conflict of the War of Independence came on 21 November 1920 which became known as Bloody Sunday. The violence of the day began with a large scale attempt by the Dublin Brigade of the IRA to assassinate thirty five members of the British Military Intelligence stationed in Ireland in order to stop intelligence being gathered on IRA members and operations. By 1920 the IRA had largely dismantled the Dublin Metropolitan Police intelligence organisation known as Division G which provided the mainstay of British intelligence. British Army Intelligence Centre in Ireland stood up a special plainclothes unit of 18–20 demobilized ex-army officers and some active-duty officers to conduct clandestine operations against the IRA and this unit became known as the ‘Cairo Gang’. While they were gathering intelligence on the IRA operatives, sources controlled by Michael Collins had already provided the names of each officer involved in the gang. The IRA also recruited servant who worked in the boarding houses and hotels the men stayed at.

On the morning of 21 November the IRA carried out operations to destroy the Cairo gang. In simultaneous assassinations twelve of the Intelligence officers as well as a number of Auxiliaries and Court Martial officers were shot. This sent the Intelligence organisation into disarray with any British officers who escaped as well as many not involved with intelligence operations fleeing to Dublin Castle.

In the Afternoon of 21 November a second atrocity took place at the Dublin versus Tipperary football match in Croke Park. A convoy of British security forces approached Croke Park and shot at ticket collectors outside the main gates. The Security forces then entered the stadium and opened fire at the crowd while an armoured car outside shot over the heads of the people rushing to escape. Major Mills in charge of the RIC men later claimed that his men lost the run of themselves and fired indiscriminately into the crowd. Fourteen people were killed and a further seventy wounded.

References

Cork Examiner, 21-22 November 1920 -

The Kilmichael Ambush

The ambush site at Kilmichael

28 November 1920A week after Bloody Sunday one of the most famous engagements in the War of Independence occurred. The Kilmichael Ambush took place on 28 November 1920.

In August 1920 the British cabinet and Dublin Castle Administration felt that training regular members of the RIC would take too long. Thus former soldiers of the First World War were hired to become temporary constables that became known infamously as the ‘Black and Tans’ due to their mismatched uniforms. The second unit founded was known as the Auxiliaries which carried out an elite counter-terrorism and paramilitary role. This unit was staffed by commissioned officers who were heavily armed and would conduct raids with impunity throughout the countryside. One hundred and fifty members of the new force of Auxiliaries arrived in Macroom in August 1920, and took over Macroom Castle as their barracks.

The Kilmichael Ambush was an operation commanded by Commandant Tom Barry of the 3rd Brigade of the IRA. Barry was a veteran of the Great War and was skilled in military planning and operations. The purpose of the ambush was to damage the image of invincibility which had sprung up around the Auxiliary Division, as well as being a response to the events of the previous week in Dublin.

Tom Barry commanded a column of 36 men who laid an ambush, with Kilmichael chosen due to the advantageous terrain. On the evening of the 28th two Crossley Tenders carrying 18 Auxiliaries were ambushed as they reached the bend at Kilmichael. Most of the men in the first vehicle were killed quite quickly, by means of rifle fire, hand-to-hand fighting and a Mills bomb. The driver of the second lorry attempted to escape the ambush but ended up in the ditch. Three Volunteers (Michael McCarthy, Jim O’Sullivan and Pat Deasy) died in the ambush with two being killed during what is believed to have been a false surrender by the second lorry load of Auxiliaries. Sixteen Auxiliaries were killed in the ambush. The IRA believed they had killed all of the Auxiliaries, but two survived.

The engagement at Kilmichael was the first between the IRA and the previously invincible Auxiliaries and has long been recognised as being one of the most important battles of the Anglo-Irish War. The British establishment could not comprehend how such a high number of battle-hardened officers fell in combat against what they previously dismissed as little more than rabble and recognised that the situation in Ireland was growing progressively violent. Due in no small part to the Ambush the Counties of Cork, Kerry, Tipperary and Limerick were placed under martial law in December 1920.

The well-known rebel song, The Boys of Kilmichael commemorates the Kilmichael ambush, and it has been sung by the Wolfe Tones, among others.

References

Cork Examiner, 30 November – 2 December 1920

Barry, Tom (1962) Guerilla days in Ireland. Anvil Books: Tralee -

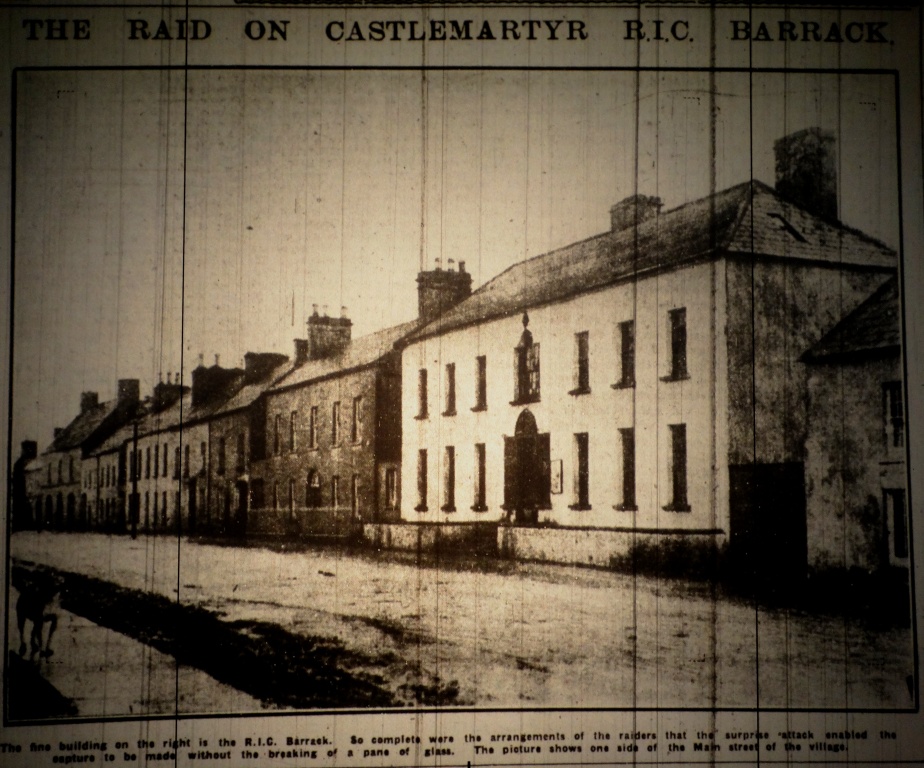

The Burning of Cork

Cork city the day after the burning

11 December 1920On Saturday 11 December 1920, Martial law was declared in County Cork. On the same morning six IRA Volunteers took up position on Dillons cross and ambushed two lorry loads of Auxiliaries of K Company left Victoria Barracks to enter the countryside north of the city. The Lorries were ambushed using Mills Bombs and revolvers which resulted in the death of one Auxiliary and eleven others wounded. Outraged at the attack, Auxiliaries from K Company proceeded to raid and burn homes in the Dillon’s Cross area. The Auxiliaries then spread out their attacks on civilians throughout the city as they made their way to the centre of the City.

Cork was one of four counties that had a Military curfew in place. Just before 10.00 pm, sporadic gunfire and bombs were reported in the city centre. Just after 10.00 pm Grants & Co, outfitters and general warehouse, on St Patrick's Street was ablaze. It is believed that the building was set on fire by the Auxiliaries who were using incendiary bombs within the city. A party of Auxiliaries also followed the trail of the Ambushers to Delaneys farm and proceeded to shoot the two Delaney brothers, Joseph and Cornelius Delaney, as well as injuring their elderly uncle. The Cork City Fire Brigade arrived and began to battle the fire. By 12.30 am the Munster Arcade and Roche’s Stores were now also ablaze. The Auxiliaries prevented the Fire Brigade from putting out burning buildings with force and fired at people attempting to retrieve property. A Contingent of the Dublin Fire Brigade under the command of Captain Myers arrived to assist. At around 6.00 am City Hall and the Carnegie Library were set alight and totally destroyed. Cook Street, Winthrop Street and Oliver Plunkett Street were almost totally destroyed and many shops had been looted of their Christmas stock. The British Military on Sunday afternoon posted armed Soldiers along Patrick Street. They also issued a warning to people not to congregate and to keep their hands out of their pockets.

It was not till 10.00 pm on Sunday night that the last of the fires were brought under control and extinguished. The main merchant section of the city was in ruin with over £20 Million worth of damage occurring. The Chief Secretary of Ireland, Hamar Greenwood, denied that the Auxiliaries were involved in the rioting, looting and burning of Cork, but because of the mounting evidence against the Auxiliaries, K Company was moved to Dunmanway and later disbanded in March 1921.

The Dillons Cross Ambush took place the day after martial law was proclaimed In Cork County by General Strickland. The six-man IRA squad from the 1st. Battalion of the Cork Brigade consisting of Captain Sean O'Donoghue and Volunteers James O'Mahoney, Michael Baylor, Augustine O'Leary, Sean Healy and Michael Kenny, ambushed a convoy from K Company of the Auxiliary Division at Dillon’s Cross. The Ambushers posted a sentry on the road before using mills bombs and revolvers on the passing troop carriers. The squad then disappeared into various safe houses in the City.

The Dillons Cross attack appears to have been the greatest motive for the burning of Cork although a detailed plan of what buildings to burn appear to have been circulated to Auxiliaries and other British forces. The attackers were seen wearing mufti (partial Civilian/military clothes) and marching in large groups down the main thoroughfares. Buildings chosen to be burned were heavily looted by the men setting incendiaries and many appear to have been drunk after looting public houses in the city centre. Civilians were assaulted and shot at by these camouflaged soldiers if they attempted to remove their belongings from houses or attempted to put out fires. In a similar vein Cork Fire Brigade members were fired at by Auxiliaries when attempting to fight the fires in the city centre even after having been posted with British Regular Soldiers as guard details. A number of fire-fighters were wounded with one being shot in the nose and another in the leg. There were also numerous reports of infighting amongst the British forces (Including the Auxiliaries, R.I.C., Black and Tans and Regular British Army) in their drunken state with one such incidence consisting of rifle fire and the use of grenades on Bridge Street between two such uniformed groups.

Sir Hamar Greenwood, immediately denied that Crown forces were responsible for the conflagration. He also refused demands for an impartial enquiry which was called for by several public bodies in Cork. In spite of Greenwood's obstinancy a booklet published by the Irish Labour Party and Trades Union Congress appeared in January 1921 entitled 'Who burned Cork city?' which, on the evidence of eye-witnesses to the events, showed that British forces had set fire to large sections of Cork city. The eye-witness depositions were gathered by Seamus Fitzgerald and the statements collated by Alfred O'Rahilly, who became the President of University College Cork in 1943. A British Army enquiry subsequently placed the blame for the fire on renegade members of a company of Auxiliaries. This Strickland Inquiry found that the British forces were responsible for the burning of Cork. The report was not published by the British Government once they received it and read its findings in January 1921.

References

Cork Examiner 12 December 1920 – 20th January 1921

O’Shea, B. & White, G. (2006) The Burning of Cork. Mercier Press: Cork

South Gate Books. (1978) The Burning of Cork: A Tale of Arson, Loot and Murder. South Gate Books: Cork.